Observations on Pacific proas by Russell Brown, Sep 3, 2011 - posted to Proa File International (groups.yahoo.com/group/proa_file)

posts by Russell Brown to proa_file forum:

Much is happening in the world of proas today, and while I'm not the worlds most technical guy, I understand a lot of how this one type of proa works and I'd like to share some of that.

My views are based on lots of practical experience, but they are just my views. Please take them as that; one person's views on one type of proa.

The traditional Pacific proas are brilliant from so many aspects. While they evolved because of the available materials, there must have also been a very fertile boat design culture to achieve such fast, light, close winded sailing machines with nothing but sticks and string.

Proas were, by far the most advanced sailing concept in the world at the time. This, because those fertile minds found ways to avoid the loads present in the structures of other multihull types. I believe their logic applies today, as much as ever.

Because I think it's the Pacific (or windward) proas strongest point, I'll start with my view of the structural issues.

The main attraction for me to this type of proa is that the concept is, in my mind, as close to structurally perfect as a multihull sailboat can get. I think of it as more of a tension / compression structure than other multihulls.

In flat water, one can be sailed as hard as possible and the structure is very lightly loaded. Yes, there's a bit of mast compression, (not so much, because of the wide staying base) and a small amount of bending load on the beams, but most of the sailing loads go to the shroud lifting the outrigger (tension). Adding water ballast doesn't load up the structure very much, and because the ballast is so far to windward, it doesn't take much.

Compare this type with catamarans or trimarans which have bending and twisting loads, and are loaded from both sides, instead of just one.

All this gets a bit more complicated when you add waves, but I think the proa looks pretty good there too.

As an example, imagine any multihull sailing hard in very rough water. Say you are close reaching at very high speeds and get launched off a wave, go airborne and then land on the leeward hull. This will cause some pretty big loads in any boat even if the boat lands level, but say you are in a catamaran or trimaran and the leeward hull buries and tries to stop the boat, this will cause twisting loads on top of all the other loads. On a proa you would land on the main hull, which carries most of the mass and is big enough to not bury the nose and not fighting another hull as much. It's more like a monohull with a lever arm to windward instead of a keel.

My first boat (Jzero) was a good study of loads for this type of proa, in that it was badly, cheaply and lightly built, and it was exposed to extreme conditions in the period that I owned it.

Jzero was made from really cheap 1/4 inch plywood, redwood stringers, and small epoxy fillets in some of the corners. This boat cost originally about $400, so that you fully understand how badly it was built. The crossarms were 5 layers of fir 1" x 4's (3/4" x 3 1/2") glued together, for a total dimension of 4 1/2" x 3 1/2" and tapering toward the outrigger. The first set of cross arms failed. They were made from 2 Hemlock 2x4's, and failed at the inboard bolt hole on the outrigger connective. Hemlock looks sort of like fir, but it's not very strong.

Mark Balogh and I went through a very bad blow in this boat in 1978, the worst weather I had ever seen (until 1997), and still, I think, the biggest waves I have ever seen. See Mark's description of this at:

www.pacificproa.com/brown/jzero78.html

This boat was raced hard and did quite well. It also went through three 100 knot hurricanes while I owned it. One was while it was anchored off the west end of St Croix, in the Virgin islands. I was not aboard, but someone else saw the boat getting towed by it's anchors through 20 foot breakers. A couple of days before this while I was trying to beat up the coast of St Croix to a safe harbor, the boat got launched off a wave, stood almost vertically, and then fell over on it's pod. The pod was built the same as the rest of the boat, 1/4" plywood and little fillets in the corners.

While I believe that this boat had more than it's share of luck attached to it, I also learned from it that the configuration is very lightly loaded.

These are just my views, but they are based on lots of experience in proas, including having to drive very hard at times. I like to take it easy when sailing offshore, as you would in a boat that is uninsured, your home, and your lifeline, but there have been times when I have had to push very hard in bad conditions.

Such as having to close reach for 100 miles in a rising gale and scary forecast, with large waves coming from three directions, to reach harbor before dark. That adventure really started trying to enter the harbor, but I had averaged over 12 knots for 100 miles in really wild conditions.

Crossing a river bar in Australia I got broached by a large breaker and thrown very violently sideways from the crest to the trough, and back again, over and over for quite a long way. This took everything inside the boat and scrambled it into opposite sides and ends of the boat.

I have always thought that the biggest loads seen on my boats has been getting hit by a breaker when beam to. Because the main hull has most of the mass and lateral resistance, it doesn't want to push sideways until the wave hits the main hull, so when a wave hits the outrigger first, things load up. This is how the first Jzero broke.

I added carbon to the crossarms of Jzerro in Australia but this was only to stiffen them. What was happening was that the main hull would shudder when the boat was slammed by a wave. This was unsettling. One would think that flexibility would soften the ride, but not in this case. The beams on Jzerro are heavily built and weigh 120 pounds each. Jzerro weighs about 3200 pounds.

The rig is my favorite, and least favorite thing on my boats. Favorite because it's so light and efficient, least favorite because it's a lot of work to tack. But the rig is really the biggest compromise of a proa, is it not? I like the idea of a cat ketch type rig with free standing masts (like Cheers has) for a cruising proa, but the cost of the spars, and the compromise in performance are not attractive. If my boat did not perform so well, what would be the point of having it?

Yes, it is work to tack, but the rig is so powerful for it's small size and can carry lots of sail in light airs.

I think that the wide slot between the main and the jib (because the mast is stepped to windward) is partly responsible for the exceptional upwind performance.

The rig has other really great things about it as well. For instance, the boat will steer itself almost to a reach. This is good when going upwind in a blow, as the boat will feather into the squalls and keep a consistent speed, (unlike with the auto pilot), and the speed is easily adjustable by raising or lowering one of the rudders or trimming a sail. The self steering is made possible, I think, by the wide separation of main and jib. The main is eased slightly, so it luffs first. The jib will pull the bow off the wind, until the main fills, and the main pushes it back up, until it luffs.

Another great thing about this rig (compared to the same type of rig on other

multihulls) is that the main can be dumped completely when overpowered when off

the wind, as there are no shrouds on the lee side for the sail to hit.

Jzerro's mast is aluminum, it's a wing section, 3 3/4" x 8 inches, it weighs 160

pounds with all the wires, and It is the same length as the boat.

Getting caught aback, while a worry, has not yet been a problem. The boat seems

to want to lie with the outrigger to windward. I have been caught aback twice

on my present boat, once while asleep in lots of wind. I was able to pull the

main down and turn the boat around with the jib.

The staying angle (headstays coming to main hull bows) is actually pretty good,

but can't really be increased without the mainsail leech contacting the headstay

(or backstay) when going upwind.

When going downwind with the main up, the main is vanged down to the pod, so

going aback would not be an issue.

When going downwind in lots of wind, the main is down and just a jib or genoa

up. This makes the steering easy (autopilot) and plenty of power. I averaged

better than 10 knots this way from the Cook islands to Fiji with just a working

jib.

To power the boat up downwind I sometimes use the main, and a genoa set free

flying and tacked to the ama bow and sheeted to the pod. This seems to work

really well at broad angles, and is easier to set and douse than the spinnaker.

Speed. I have never had a proa that had good sails and was tuned up for racing

and usually my boats are loaded with lots of cruising gear, but I have done

enough racing to know that it takes a very fast boat to beat the boats I've had.

The passage that Mark Lamb and I did from Australia to New Zealand is a good

example of upwind speed. The first 350 miles were good sailing, and then it was

strong headwinds for the remaining 700 miles, including 2 1/2 days of heading

slowly towards Antarctica. This passage took just over 6 days.

What makes these boats so fast and weatherly? Certainly not high initial

stability and raw horsepower. Maybe it's what Steve Callahan called "spiraling

down the path of least resistance".

Longitudinal stability. Sailing nose down is something that all proas seem to

do. This is another thing on the list of proa compromises that's difficult to

get around.

On any multihull, the leeward bow is what resists the forward drive from the

rig.

With most of the weight, volume, and buoyancy in the main hull, the windward

proa configuration works well at resisting nose diving. Even still, things can

get a bit weird on my boats, but only when broad reaching with way too much

sail, trying to see how fast you can go.

My fear of nose diving is why my boats have such big noses. I guess that fear

has payed off, because it's not something that I worry about at sea.

A friend of mine is designing a racing proa with articulating crossarms, so that

the ballasted outrigger hull can be moved aft when pushing hard.

The Pod. One probably wouldn't sail this type of boat in the ocean without one.

First, because it makes for a usable interior and a wonderful place to sleep,

and second, because it would be unsafe.

I say this even though in my present boat I have never had a knockdown. On my

last boat I did have a couple of serious ones; One going fast with the

spinnaker sheet wrapped around the tiller, the other in 60 knots of wind (said

the nearby coastguard station). In both of these knockdowns the boat was

pinned over for a period of time. On my first boat, with a small pod, I had a

couple of serious knockdowns as well, one in quite rough weather.

The stability curve is quite a bit different than with other multihulls. In static conditions, these boats balance with the mast below horizontal, (past 90 degrees) this is because the whole main hull is lifted out of the water by the pod when you lean it on it's side. Keeping heavy things, such as water tanks, in the bilge of the main hull adds to this reserve stability. I'm not saying these boats are safer than anything else, because I don't know, but I have had some pretty serious knockdowns, and have not tipped over.

Water ballast. Who could argue with water ballast in a proa? It is always on the windward side of the boat, and it's so far out there that it doesn't take much of it. Adding ballast is easier than reefing, and the boat can be driven really hard with just a bit of ballast.

Steering. The rudders that I have used on all my proas are very similar to the

rudders that Dick Newick devised for Cheers 45 years ago. These rudders are

retractable and fit in trunks like a daggerboard. Like a daggerboard they are

vulnerable to damage, but unlike the daggerboards in most multihulls, the trunks

are separated from the rest of the hull in both directions by watertight

bulkheads to prevent flooding in the event of an impact that damages the trunk.

These rudders are small, yet provide very positive control. They are skeg

rudders, so bending loads are taken by the skeg. The skeg doesn't help with low

speed steering (I sometimes use both rudders for maneuvering), but the skeg adds

much to high speed control. The skeg rudder is also very effective at creating

lift if there's weather helm present. When going upwind, the forward rudder can

be dropped just a bit to create weather helm. The aft rudder, having the skeg in

front of the blade (looks like a wing sail in section), is a powerful lifting

foil.

The rudders, while complicated to build, have been virtually trouble free on all

my boats.

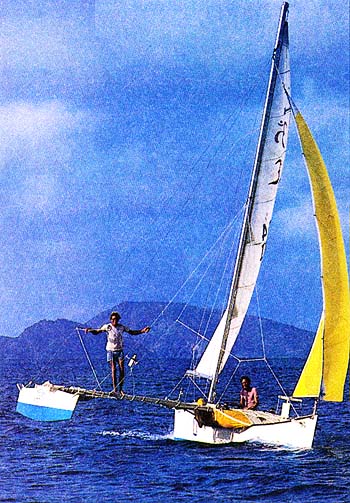

One of the misconceptions about these boats is that they often fly the outrigger

hull.

One of the misconceptions about these boats is that they often fly the outrigger

hull.

It's fun to fly the hull when goofing around and the magazines tend to pick only

the dramatic photos, which has helped lead to this misconception.

The outrigger hull does fly over the troughs when driving hard upwind, but in

the ocean the boat is kept positively balanced.

None of my boats have ever had a well designed outrigger hull. I would like to

build an outrigger hull for my boat similar to the one on Harmen Hielkema's proa.

I have sailed on this boat and was very impressed. The outrigger hull was designed by Mike Toy. It is really beautiful and it doesn't have the bad habits that mine does.

An outrigger like that would be longer than the type that I have been using and

could much more gracefully carry extra weight or ballast. A wave piercing

shape, even though longer, might not add to the already minimal twisting loads

on the structure.

I don't see that the outrigger on a windward proa needs to contribute to

longitudinal stability.

I look at proas now with an ever widening view of their advantages and

disadvantages, compromises, and possibilities.

I also know from experience that there's some real magic to this ancient

configuration.

It has been a blast fooling around with these boats, but proas have a long way

to go.

I hope that my observations help in the future development of these boats.

All the best,

Russell

-

JZERO of Polygor, 1977

- photos by Craig Bumgarner

JZERO of Polygor, 1977

- photos by Craig Bumgarner

- JZERO of Polygor, 1978 Sailing to Puerto Rico with Russ Brown by Mark Balogh

- KAURI: Photos, text, and video! 37' proa on Martha's Vineyard, 1989 by Joseph Oster

- Park It, Dad by Jim Brown - Russell and Jim sail KAURI from Bermuda to New England *Sep, 2011

- CIMBA (re-named Pacific Bee in 2008) and JZERRO

CIMBA becomes Areté, Chiloé Island, Chile *Feb, 2020For Sale, January 2023 - JZERRO Construction Photos Port Townsend, WA 1992 by Joseph Oster

- JZERRO Mexico Photos... 36' Pacific proa, Baja California (Mexico)

- a sailing 'push me-pull you' JZERRO article by Andy Turpin, Latitude38

- JZERRO "doing about 20 knots"

on S.F. Bay, passing Profligate,

Dave Culp and Joseph Oster visible on bench seat, Latitude38 - Photos! Sailing JZERRO on San Francisco Bay

Russell Brown, Jim Antrim and Joseph Oster, June, 2000 - Russell Brown on Proas interview w/ John Harris at clcboats.com

"Jzerro will reach at 17 or 18 knots in 12 knots of wind." - JZERRO haul out Dec 2013, Port Townsend, WA

JZERRO on video

Pacific Proa Jzerro in Port Townsend - September 2012

Jzerro underballasted and hard on it

Proa Jzerro September, 2011

sailing 17.8 knots on auto-pilot!

720p HD

*posted May, 2011

sailing 17.8 knots on auto-pilot!

&

sailing past lighthouse

*posted July, 2008 (not HD)

Jzerro in Port Townsend 2015, at 18 knots

EPOXY BASICS: WORKING WITH EPOXY CLEANLY & EFFICIENTLY

by Russell Brown

Other Proa Pages